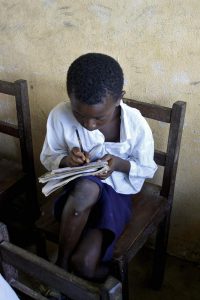

Cestos City – Twelve-year-old Baby Girl Yarkah is in the first grade and attends the Upper Timbo Community School in Little Liberia, Rivercess County. She shares a small chair with another girl because there are not enough seats to accommodate the school’s 200 students. The chairs have no arms. There are no desks at all.

Part 2 of a 3-part series on Liberia’s Rural Education Crisis by Front Page Africa’s Mae Azango in collaboration with New Narratives. Photos by Chase Walker.

“The chairs are not plenty for us, so we can sit two on a seat, and this can give us hard time to write,” said Yarkah.

Yarkah is one of the lucky ones. Some of her classmates must stand or sit on cement blocks or the floor. Students of different grades often cram together and share classrooms. This interferes with the children’s learning processes since their bodies cannot relax, said Labbie Williams, chairman of the Parent-Teacher Association (PTA). Yet there is no choice but to make do.

“It is better to group the children for them to have a little knowledge than to have them not come to school at all,” said Williams.

The lack of adequate school buildings and materials in Rivercess makes the environment difficult for students to learn. For the investigation of our educational system, FrontPage Africa/New Narratives spent a week in this rural part of Liberia. Experts say Rivercess is one of many rural counties struggling to make ends meet to educate its children.

“We have overcrowded classrooms with 45 students, and they are clustered together,” said Jacob Kouviakoe, district educational officer (DEO) of Monweh District, Rivercess County.

In Little Liberia, the old, five-classroom Upper Timbo School was built of mud and brick by the community with the help of an NGO in 2000. There is no glass for windows, just gaping empty frames on both sides of a classroom exposing students to water and wind during rainy season.

Hannah Gaysayee, 19, is in the sixth-grade class and shares a chair with another student and a classroom with fifth graders.

“The lesson you will take in fifth grade is the same lesson you will take when you pass to sixth grade class,” said Gaysayee.

Because of limited space, first and second graders are combined in one classroom as well, as are third and fourth graders. In each classroom, there is the same noticeable lack of chairs.

Our investigation discovered that there are chairs designated for Rivercess County schools. However, they sit unused – locked in the storage houses of companies contracted by the Ministry of Education to repair chairs. The Ministry has not provided transportation or transport money to deliver the chairs to the schools.

“We have gotten less than 400 chairs for my district, and it is not enough for 37 schools,” said Kouviakoe. “I have gone to the companies that are contracted to fix the chairs and asked them to send the chairs to my district, but they have not done it yet.”

According to the Ministry of Education 2010-2011 Census Report, Rivercess should have received 628 chairs, 520 table benches, 440 desks, 453 chalkboards, and 29 computers. But the report does not specify how many of these items actually made it to the schools. The educational officers to whom we spoke say they have received nowhere near those amounts.

Similarly, little government assistance has been provided in terms of school construction. Of the 126 schools in Rivercess, most are church buildings or makeshift structures built by the communities themselves and the local PTA. The better schools are built by NGOs, never the Ministry of Education, according to the district education officers we interviewed.

“We have only two modern constructed schools built by the European Union and FAWE,” said Kouviakoe. “Other communities erect schools with baboon sticks and thatched roofs on their own. We have been telling the government about these things but no redress.”

DEO Cheyee Kpanwone told a similar story of the 18 public schools and one mission school in Yani District.

“Most of the schools are makeshift and constructed by citizens,” said Kpanwone. “We teach in open classrooms without partition. It is like a living room – that is interrupted by other teachers – constructed.”

The construction materials for these schools are mud, brick, sticks and leaves for a thatched roof. Only one school built by FAWE is up to standard and spacious with nine classrooms.

Whatever the district, the schools are few and far between.

“I have 37 schools in Monweh District, and the schools are like two hours walk from one another,” said Kouviakoe.

There is only one high school for the entire county, even though its total area exceeds 2,000 square miles. The majority of youths must walk many miles if they want to get more than just a basic primary education. Some must first find a way to cross the river and then walk another 45 minutes to get to school. Many just drop out.

Speaking on behalf of the government, former Deputy Education Minister for Instruction Mator Kpangbai said the government’s hands are tied by lack of funds.

”Government cannot put a school in every village or town, because we do not have unlimited resources and there are no roads to build junior and senior high schools,” Kpangbai said during an interview in his education ministry office last year. “We do realize that it is taking us a long time to do these things, but as the government budget improves, we will certainly bring about the qualified teachers and the construction of more classrooms.”

There is no separate educational budget for each county, but the total educational budget for the entire country is about US $40 million, according to Kpangbai. Most of this money is used to pay staff.

“About 80 percent of our budget is for personnel, so the discretionary fund we have is so small, and we have to use it wisely,” said Kpangbai.

Scarcity of instructional materials and instruments poses another challenge for Rivercess County schools. Even free notebooks provided by children’s charity UNICEF are insufficient for all the students.

There are barely any textbooks in libraries for students to study, and the ones that line the shelves are in poor condition. At Cestos High School, we found one particularly old, worn book that had crumpled pages covered in toxic black mold and stuck together.

“The reading room and science laboratory are not equipped,” said Gabriel Dossen, administrative assistant to the county education officer of Rivercess County. “In the reading room, there are no prescribed textbooks, just all outdated American textbooks.”

“The science lab has nothing in it but an empty room. You cannot even find one faucet, table or any instrument in it. Common table salt and Clorox formula – the students don’t know it.”

Even the administration offices have not been supplied with working equipment such as computers, typewriters or photocopiers. Dossen said he has written to the government requesting these essentials, but nothing has been done.

Former Minister Kpangbai said the shortage of chairs, instructional materials and space is a nationwide issue.

“This is not a Rivercess issue but a larger problem, but as time goes by, we will improve the system,” said Kpangbai. “In the future, I am sure when the ideal oil revenue comes, we all will have the ideal educational system we will need.”

Kpangbai did not specify an exact timeframe. So while the government awaits the ideal future, the students and teachers of rural areas like Rivercess must continue to contend with a less than ideal present.

Mae Azango is a fellow of New Narratives, a project supporting the businesses of leading independent media in Africa. See more at www.newnarratives.org. New Narratives and FrontPage Africa traveled to Rivercess in 2012.